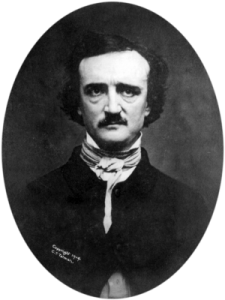

More than one thousand souls, many of them luminaries from Baltimore’s storied past, lie buried within the brick walls of Westminster Burying Ground, and there is reason to think that the spirits of many of them haunt its grounds. For most people, however, the place is significant as the final resting place of writer Edgar Allan Poe—who, to his innumerable other distinctions, can add being buried three times and having his final resting place marked at two different spots in the eighteenth-century graveyard.

More than one thousand souls, many of them luminaries from Baltimore’s storied past, lie buried within the brick walls of Westminster Burying Ground, and there is reason to think that the spirits of many of them haunt its grounds. For most people, however, the place is significant as the final resting place of writer Edgar Allan Poe—who, to his innumerable other distinctions, can add being buried three times and having his final resting place marked at two different spots in the eighteenth-century graveyard.

When it was established in 1786 by a prominent local Presbyterian congregation, the burying ground lay to the west of the Baltimore city limits and was located there due to fears of contagion that were not completely unfounded.

“Four of the city’s earliest mayors, including the first, James Calhoun, are buried here, as are a number of generals of the American Revolution and the War of 1812, eighty lesser officers, and more than two hundred other veterans,” a pamphlet published by the Westminster Preservation Trust says. “Hollins, Gilmore, Stricker, Ramsay, Stirling, McDonogh, Calhoun, Bentalou, Sterrett . . . all share the distinction of having Baltimore streets named in their honor.”

A church was not originally built on the site and was not added until six decades after the first bodies were laid to rest there, both to meet the needs of the growing congregation and to help protect and maintain the burial ground. Completed in 1852, Westminster Presbyterian Church was a Gothic Revival structure that had a number of interesting architectural characteristics that make it exceptional if not unique.

Foremost among these is that the church was constructed on brick piers over many of the tombs, giving the impression that they are located in underground catacombs. Numerous large family sepulchers and individual grave markers, many of them crumbling, darkened with age, and ivy-covered, fill the walled yard surrounding the building as well, creating a compact and somewhat confined little necropolis. While “Gothic Revival” will undoubtedly spring to mind for a small proportion of visitors, “Gothic Novel” will resonate for many more, and those are by no means the most interesting or eerie attributes of the place.

When Edgar Allan Poe died in 1849 at the age of just forty— under mysterious and somewhat suspicious circumstances that are disputed to this day—he was buried in an unmarked grave in the Poe family plot near the back of the Westminster Burying Ground. Today, a gravestone near a number of other Poe graves—including that of his grandfather, General David Poe Sr. and his brother, Henry Leonard Poe—bears his name and is thought by many to be where he was buried prior to being relocated to the ground beneath the more impressive marker near the front of the graveyard.

“That is not his original burial place. He was actually moved twice,” Luann Marshall, tour director for the site, explained to me. Poe’s fame and the affection admirers of his work felt for him grew posthumously, and when these sentiments were matched with sufficient funds, a large monument to him was purchased. It was too large, however, to fit on the plot in which he was buried, and the author had to be disinterred and was reburied elsewhere in the family plot in April 1875.

“That is not his original burial place. He was actually moved twice,” Luann Marshall, tour director for the site, explained to me. Poe’s fame and the affection admirers of his work felt for him grew posthumously, and when these sentiments were matched with sufficient funds, a large monument to him was purchased. It was too large, however, to fit on the plot in which he was buried, and the author had to be disinterred and was reburied elsewhere in the family plot in April 1875.

“People would come in to pay their respects and would search for his gravesite but couldn’t find it, even after his fans went to all the trouble to put the monument on his grave,” Marshall told me. “So, in November of 1875, they purchased the plot just inside the cemetery gates from the family that owned it and moved him there so that people would be able to see him as they went by.” This monument, which cost six hundred dollars at the time, was paid for by Baltimore schoolchildren collecting “pennies for Poe,” and today it is customary for visitors to leave one cent coins on the white stone marker. Another interesting fact associated with this monument is that the inset bronze medallion bearing Poe’s likeness is a replacement for a marble original, which was stolen and eventually turned up in a flea market in Charleston, West Virginia, and was subsequently donated to the Poe House in Baltimore, where it is periodically on display.

A much smaller gravestone—bearing the image of a raven, which has become both the symbol of Poe and the city of his death—now marks the second spot where he was buried. One can only imagine that Poe would probably have profoundly appreciated not just the fame his work eventually enjoyed but also the morbid details, so reminiscent of scenes from his own stories, associated with the disposition of his remains.

In the decades following the reburial of the churchyard’s most famous celebrity, the Westminster Presbyterian Church struggled to remain viable and, by the centennial of the new marker had, sadly, dwindled to almost nothing. In 1977, it was turned over to the Westminster Preservation Trust, a private, nonprofit group established under the leadership of the University of Maryland School of Law, and its days as a house of worship came to an end.

Today, the place is known as Westminster Hall, which has been fully restored by the trust and is now used for secular purposes that include tours of the “catacombs” and graveyard.

The most visited spots in the graveyard are, of course, the ones dedicated to Poe, which have virtually risen to the status of pilgrimage sites. Associated observances include an annual birthday celebration at the hall hosted by the nearby Edgar Allan Poe House and Museum each January on the weekend closest to his birthday (an event that, in 2009, observed the two hundredth anniversary of the author’s birth). And, every year on January 19 since 1949, a mysterious individual has come to Poe’s grave, left three roses and a half-filled bottle of Martell cognac—believed to have been the author’s favorite drink—and made a toast to him (there is evidence that the original toaster died in 1998 and that the role was subsequently bestowed upon a successor). The roses are generally believed to represent Poe; his wife, Virginia; and his mother-in-law, Maria Clemm—all three of whom are buried in the churchyard. The toaster has sometimes also left notes, many of them cryptic and, in recent years, sometimes even controversial (e.g., an apparent dig at the French in 2004).

The most visited spots in the graveyard are, of course, the ones dedicated to Poe, which have virtually risen to the status of pilgrimage sites. Associated observances include an annual birthday celebration at the hall hosted by the nearby Edgar Allan Poe House and Museum each January on the weekend closest to his birthday (an event that, in 2009, observed the two hundredth anniversary of the author’s birth). And, every year on January 19 since 1949, a mysterious individual has come to Poe’s grave, left three roses and a half-filled bottle of Martell cognac—believed to have been the author’s favorite drink—and made a toast to him (there is evidence that the original toaster died in 1998 and that the role was subsequently bestowed upon a successor). The roses are generally believed to represent Poe; his wife, Virginia; and his mother-in-law, Maria Clemm—all three of whom are buried in the churchyard. The toaster has sometimes also left notes, many of them cryptic and, in recent years, sometimes even controversial (e.g., an apparent dig at the French in 2004).

I visited Westminster Hall and Burying Ground for the first time in May 2009 with a dozen members of the Inspired Ghost Tracking paranormal group. The first thing that struck me upon entering the graveyard that damp, drizzly Saturday evening was how reminiscent it was of some of the above-ground cemeteries I had visited in Europe, notably Père Lachaise in Paris. True, it was not nearly as large as the Old World burial grounds of that ilk that I had visited (although it was, overall, much better maintained).

But the dark, moldering stone sepulchers and markers, all jammed together into a tiny, mazelike microcosm, created a minuscule world of the dead within a city of the living which, it seemed to me, could not help but be haunted.

We were not, suffice it to say, disappointed. Almost immediately upon arriving at Westminster Hall, Inspired Ghost Tracking group-organizer, Margaret Ehrlich, and two of her friends, Ross and Amy Twigg, heard organ music coming from the former church, which is the home of a fully restored 1882 pipe organ. Upon revealing this, however, to Luann Marshall, the Westminster Hall representative overseeing our tour, they learned that the building was completely locked up and that no one was in it! This particular phenomena is, it turns out, one that is regularly reported at the site.

Over the next couple of hours, we collectively experienced a number of other phenomena of an apparently paranormal nature while exploring the site. These included detection of the presence of spirits by some of the sensitives in the group, the capturing of several very profound orbs by several members of the group, and one of Margaret’s assistants, Maria Blume, becoming overwhelmed by the spiritual energy in the catacombs and having to leave them.

I myself took a picture of one member, Wendy Super, and was stunned to see a large, substantial green orb appear in the image beside her! When I somewhat excitedly told her about this, she very calmly explained that she is a Reiki master who specializes in helping earthbound spirits cross over to the afterlife and that it is common for them to gravitate to her as someone who is able to help them.

I myself took a picture of one member, Wendy Super, and was stunned to see a large, substantial green orb appear in the image beside her! When I somewhat excitedly told her about this, she very calmly explained that she is a Reiki master who specializes in helping earthbound spirits cross over to the afterlife and that it is common for them to gravitate to her as someone who is able to help them.

A number of other members of the group reported similar experiences. “I kept feeling activity in that area; that is why we asked Ross to come over as well,” said Brenda, an Inspired Ghost Tracking member, of a particular section of the tombs beneath the former church and the photographs she and some of the others took there. “It looks like Ross and I were having an orb meeting.”

Luann Marshall, who has worked at the site for nearly three decades, told me a number of other incidents people have experienced at it over the years. She herself has on more than one occasion suddenly felt the hair on the back of her neck stand up and experienced a feeling akin to panic while in the covered crypt and dispelled it merely by stepping outside. And, she said, during the filming of some footage at the site, the cameraman told her that he had felt someone touch him on the shoulder and whisper in his ear, “Go away!” There was, of course, no one visible around him, and he was understandably shaken by the experience.

We also learned a number of nonparanormal facts about the place that contributed to the macabre aura that surrounds it. One of the strangest involves the local water table, which rises dramatically during heavy rain. Historically, this would cause interred bodies—which in the past were frequently buried just two or three feet below ground—to rise to the surface and sometimes be carried by the flowing waters through the streets and into the nearby residential and commercial areas of the city.

This problem was addressed by placing heavy stone slabs on the ground over areas where bodies were buried. It could not remediate the situation in a crypt beneath the main part of the “catacombs,” however, where until even a few years ago the rising waters would lift a coffin that has since finally disintegrated.

On one occasion during a tour of the place, Luann Marshall told me, the floating casket kept banging against the walls of the crypt, much to the horrified delight of the middle school students witnessing it. Talk about a scene straight out of a Poe story! And just an hour before we had been irritated that it was raining at all, and now some of us were disappointed that it was not a significant enough downpour to create any similarly ghoulish effects.

The lack of such melodrama did not dampen our enthusiasm, however. Westminster Hall and its graveyard are, in short, incredibly fertile ground for paranormal investigators, history buffs, and fans of horror literature alike, and are much more accessible than many sites of similar age and significance.

Their atmosphere and history alone are enough to ensure a fruitful and enjoyable visit, and it is hard to envision a group of ghosthunters who would not find the experience incredibly worthwhile. But it is an open question whether any spirits they encounter would include that of Poe or merely those of prominent Baltimoreans whose fame has been eclipsed by that of the city’s most renowned poet.

More haunted tales connected to Edgar Allen Poe are found in Ghosthunting Maryland by Michael Varhola.