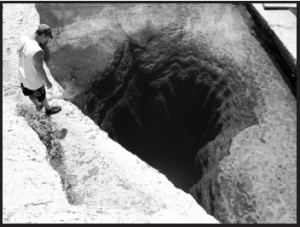

Michael O. Varhola, author of Ghosthunting San Antonio, Austin, and Texas Hill Country, takes us to the mysterious Jacob’s Well in Hays County.

Michael O. Varhola, author of Ghosthunting San Antonio, Austin, and Texas Hill Country, takes us to the mysterious Jacob’s Well in Hays County.

Peering into the mysterious and ominously beautiful depths of Jacob’s Well, it is almost hard to believe that it is not haunted. Native Indians certainly held this natural artesian spring, which rises up through a limestone tube from the unmeasured depths of the underworld, to be sacred and inhabited by elemental spirits of the land. Beyond its appearance and hallowed nature, however, it is also the site of numerous drownings, and there are those who believe the ghosts of those who have perished at this spot continue to haunt it.

Jacob’s Well, the mouth of the spring that forms the headwaters of aptly named Cypress Creek northwest of the village of Wimberley, has traditionally served as a swimming hole for locals living on the adjacent properties. Today it is a natural area that is open to the public and still a popular swimming spot—albeit one that is closed for several months a year so that it can recover from the environmental damage inflicted by people who use it.

While the spring coming up through Jacob’s Well remains a significant source of water for people living in the area, its flow is by no means as profound as it once was. In 1924, for example, so much water surged up through the spring that it shot 6 feet into the air and its discharge was measured at 170 gallons per second. Today, however, as the result of development in the region and the heavy burden placed on the local aquifers, the flow of water from its depths manifests itself only as a faint ripple on the surface of the pool. It has even stopped flowing twice in the past couple of decades, the first times it has done so in recorded history, first in 2000 and then again in 2008. In an attempt to help protect the viability of the spring, Hays County purchased 50 acres of land around Jacob’s Well, and the Wimberley Valley Watershed Association subsequently transferred an additional 31 acres from the natural area to the county.

At its mouth, Jacob’s Well is 12 feet in diameter and descends vertically for about 30 feet, at which point it disappears into the darkness of the limestone caverns from which it issues. Thereafter it descends at an angle through a series of four silted chambers separated by narrow passageways to a depth of about 120 feet. The first two chambers are relatively safe and manageable for trained divers, but the next two are increasingly dangerous, with hazards that include loose debris in both and a dead end in one that can be confused with the exit tunnel and led one diver to become trapped and killed in 1983. After the fourth chamber, the cavern becomes a tunnel that continues for about 4,300 feet (e.g., more than 0.8 mile). At least one large secondary trunk splits off from this main passageway and extends for about another 1,000 feet.

At its mouth, Jacob’s Well is 12 feet in diameter and descends vertically for about 30 feet, at which point it disappears into the darkness of the limestone caverns from which it issues. Thereafter it descends at an angle through a series of four silted chambers separated by narrow passageways to a depth of about 120 feet. The first two chambers are relatively safe and manageable for trained divers, but the next two are increasingly dangerous, with hazards that include loose debris in both and a dead end in one that can be confused with the exit tunnel and led one diver to become trapped and killed in 1983. After the fourth chamber, the cavern becomes a tunnel that continues for about 4,300 feet (e.g., more than 0.8 mile). At least one large secondary trunk splits off from this main passageway and extends for about another 1,000 feet.

Many divers have been drawn to explore and map these water-filled subterranean tunnels, but, because many of them do not have the necessary experience or equipment and the area is inherently hazardous, at least nine of them have died here since the 1970s.

“This is the horror story side of it,” Don Dibble, a dive shop owner with more than four decades of diving experience, said in a 2001 interview with writer Louie Bond. “Jacob’s Well definitely has a national reputation of being one of the most dangerous places to dive.”

“Dibble has pulled most of the victims’ remains out of Jacob’s Well himself, and he nearly lost his own life in a 1979 recovery dive,” Bond wrote. “Dibble was attempting to retrieve the remains of two young divers . . . when he became trapped, buried past his waist in the sliding gravel lining the bottom of the well’s third chamber. Just as he ran out of air, Dibble was rescued by other divers but suffered a ruptured stomach during his rapid, unconscious ascent.”

Dibble tried to block access to the entrance of the third chamber by constructing a grate made from rebar and quickset concrete in early 1980. Six months later, however, he discovered not just that the barrier had been removed but that the well-equipped people who did so had taken the time to taunt him.

“You can’t keep us out,” they wrote on a plastic board that they left behind for him. Perhaps not. But, in the case of some of them, inexperience, bad luck, the guardian spirits of the spring, or some combination of those things have ensured that they did not leave.

“We were not looking for human remains,” Dan Misiaszek of the San Marcos Area Recovery Team wrote in his account of a 2000 foray into the perilous fourth chamber. “I first noticed one femur bone, then a second, and as I descended into the keyhole-shaped tunnel, I could see a heavily corroded scuba tank and wetsuit. It was obvious we had stumbled upon some human remains . . . The tank was still attached to a [wet suit] with weight belt.” Nearby he found a human skull and, farther on, evidence pointing to the identity of the person who had suffered a terrifying death there, alone and in the impenetrable darkness that would have been imposed by the disturbed silt.

Ironically, it is the reduced force of the spring that has in recent times allowed people to dive into it; prior to the 1970s, the flow of water would have largely prevented them from doing so. People using makeshift gear attempted to descend into the spring in the 1930s, for example, but the deepest they were able to go was about 25 feet. None of them is reported to have been killed. It is almost as if a reduction of the striking site’s inherent power has led to a proportionate increase in its lethality.

“It’s a very mysterious place, a place of constant sensation,” said author Stephen Harrigan, who wrote an acclaimed 1984 novel titled Jacob’s Well that explores the death of a diver at the site.

I can only agree with Harrigan. Staring into Jacob’s Well when I visited the site in early September 2014 was like looking into an eye that was the window to the soul of the Texas Hill Country itself. After a point, it was hard not to blink or look away, and I half expected to see the shadows of the dead or elemental spirits of the land swimming up toward me from the primordial depths. That they reside there is something I do not doubt.