Michael J. Varhola, author of Ghosthunting Virginia, thinks there is something strange going on at the Exchange Hotel Civil War Hospital Museum in Gordonsville. Here is his report!

My interaction with museum staff when I visited the site in May 2008 with my father, mother, and wife left me inclined to believe that there was a reasonable chance the site was, indeed, haunted. But when I heard the irregular, garbled sounds that obscured my one-hour taped interview with curator Robert Kocovsky, I joined the ranks of definite believers.

This did not make me in any way unique, of course. The Exchange Hotel has for some time run ghost tours of the property for those with a casual interest in the subject, and it has made provisions for ghosthunters and others with a stronger interest to conduct investigations overnight in the building. From what I understand, they are rarely disappointed.

A new era began for Gordonsville on January 1, 1840, when it became a stop on the Louisa Railroad—renamed the Virginia Central 10 years later—allowing passengers to travel to and from the town and goods to be shipped from the farms and plantations of the surrounding area. Its first depot was opened in 1854, at the south end of Main Street, when the Orange and Alexandria Railroad extended its tracks from Orange to Gordonsville to connect with the existing line (a second depot was built in 1870 and its last one in 1904).

People coming into or departing from the depot frequented the nearby tavern run by Richard F. Omohundro, who did a brisk business in food and drink. When this establishment was razed by fire in 1859, Omohundro immediately built a beautiful new hotel, complete with high-ceilinged parlors and a grand veranda, on its ashes.

The elegant, three-story Exchange Hotel combined elements of Georgian architecture in the main section of the brick building and Italianate architecture in its exterior features, both styles popular in the pre-war years. Other features included a restaurant on its lower level, spacious public rooms, a central hall with a wide staircase and handsome balustrade, and central halls running through each of the upper floors. It quickly became a popular and inviting spot for travelers.

When the Civil War began in 1861, towns like Gordonsville and the railroads that ran through them became critical strategic assets to the Confederate government. Railroads had never been used in warfare before but were to play a large role in the conflict that would eventually become referred to as “the first railroad war.”

In March 1862, the Confederate military authorities took over the Exchange Hotel and established it as the headquarters of the Gordonsville Receiving Hospital, which provided medical care to tens of thousands of Northern and Southern troops over the following four years. Wounded soldiers from battle- fields that included Brandy Station, Cedar Mountain, Chancellorsville, Mine Run, Trevilian Station, and the Wilderness were brought into town by rail, unloaded, and moved directly into the sprawling hospital compound that grew up around the former hotel.

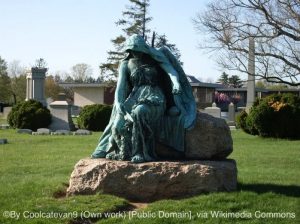

In an era when men died of injury and disease in droves—about twice as many as those slain in combat—the Gordonsville Receiving Hospital was the exception to the rule, with a markedly lower death rate compared to most other contemporary medical facilities. Of the approximately 70,000 men treated at the hospital, only somewhat more than 700 died at the site, a much smaller proportion than what was typical for the conflict. The deceased were buried on the hospital grounds initially and then later exhumed and moved to the nearby Maplewood Cemetery. (According to Kocovsky, the spirits of some of the buried soldiers apparently remained behind, and the area where the cemetery was located has been the site of ghostly phenomena.)

The director of the hospital was Dr. B.M. Lebby, who oversaw its operations through October 1865. Although pro-Confederate and a native of South Carolina, Lebby had received his medical training in the North and was both compassionate and proficient. The relatively low death rate at the hospital (a mere 26 Union soldiers) can be attributed to his humanity and skill as a physician and administrator.

After the war, the site served newly freed slaves as a Freedman’s Bureau Hospital for several years before eventually reverting to use once again as a hotel. In 1971, Historic Gordonsville Inc., acquired the property, restored it, and converted it into a Civil War medical museum.

Today, the Civil War Museum at the Exchange Hotel contains exhibits on the history of Gordonsville, the hotel, and its transformation into a receiving hospital, the only one still standing in Virginia. It includes an impressive collection of artifacts relating to medical care during the war, including surgical instruments; pharmaceutical bottles and containers; medical knapsacks and panniers; stretchers and litters; prosthetic devices; and even dental tools.

It is also home, Kocovsky said, to at least 11 ghosts that he and the staff have identified! The museum makes no secret of this presence and touts it both in its published materials and highly popular ghost tours.

“It isn’t necessary for our guides to purposefully frighten you, as our ‘permanent residents’ often make their presence known,” the tour description reads. “There have been numerous reports of apparitions, as well as the many unexplained sounds described by past visitors.”

While not all the ghosts have been identified by name or connected with specific historical figures known to have been associated with the Exchange Hotel, quite a few have, in part through the help of ghosthunters and psychic researchers who have visited the site.

One such ghost is Annie Smith, a black woman and the hotel’s former cook, who has been spotted numerous times in the windows of and around the outbuilding used as a summer kitchen where she worked. Another is Mrs. Leevy, the wife of one of the doctors assigned to the hospital, who went mad during her stay at the site. And yet another is the aptly named George Plant, the facility’s gravedigger, who has been known to waken reenactors camping out on the grounds surrounding the hotel. A number of nameless ghosts, believed to be those of Civil War soldiers who died at the hospital, quite possibly in agonizing surgical procedures or of one of the diseases that claimed so many lives, are also among those that haunt the site.

Kocovsky also told me about a dark, shadowy, and hostile ghost—whose name is yet unknown—who has frightened a number of people over the years, including, on one occasion, some police officers who were checking to make sure the building was properly locked up.

Other ghostly incidents people have reported at the museum include sightings of a spectral woman sitting as if upon a chair, even though one was not there, and photographs that have picked up a number of anomalies, including spirit orbs.

Despite the vast number of incidents that have occurred at the Civil War Museum at the Exchange Hotel, it is, unfortunately, a bit much to expect that one should experience anything similar during any particular visit (especially a first one, it would seem). Indeed, the museum itself echoes this sentiment in its materials: “As it is impossible to predict when these ‘permanent residents’ will make their presence known, we urge you to visit often.”

Good advice indeed. Because if the strange, incomprehensible sounds—voices?—on the tape I walked away with is any indication, then the museum is well worth further investigation.